MGM’s early movies are very, very white.

Except…unfortunately…for those moments when someone like Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland or even Joan Crawford appeared in black face. And those moments are hard to watch.

Very few African Americans took center stage at MGM in the years before the 1960s. And it’s really too bad. I can only imagine the amazing talent that was never discovered because of the color of one’s skin.

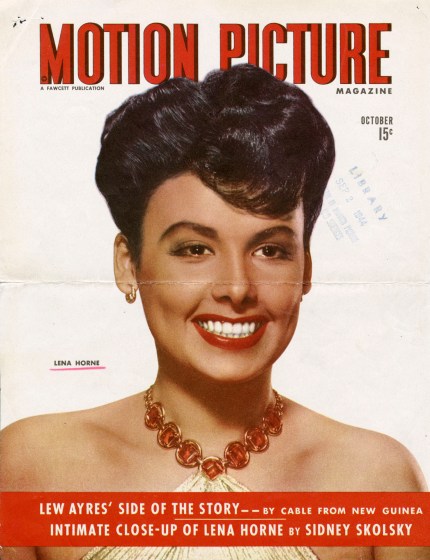

But Lena Horne was an exception. She was the first black woman to get a contract at a major Hollywood studio and would be known for having one of the most distinctive and beloved voices in show business. And she would spend her entire life fighting the racism that kept her from truly soaring.

By 1941, Hollywood was being pressured by the NAACP to cast a black actor in a non-stereotypical role – those roles were the subservient roles like servants and Pullman porters. Horne was the perfect woman to break this barrier, but it wasn’t easy.

Born into a black bourgeoisie family in 1917, Horne was groomed for greatness by her grandmother, a college graduate. The Hornes owned a four-story residence in the Bedford-Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn. The distinguished Horne family included teachers, activists and a Harlem Renaissance poet.

Horne had also been a member of the chorus line in The Cotton Club in 1933 at age 16. So with her experience, a friend got her an interview with Arthur Freed at MGM. In January 1942, MGM signed Horne to a seven-year contract. She would get $350 a week the first year and $450 the following years. Her contract stipulated that she would sing in pictures and play legitimate roles – not as cooks or servants.

But that wasn’t going to be an easy sell…especially in the South. And the bottom line was what L.B. Mayer, the head of MGM Studios, was mostly interested in.

She appeared in Panama Hattie and an all black musical, Cabin in the Sky. Horne’s first scene in Cabin called for her to sing a song while reclining in a bubble bath. After the pre-release the censors demanded cuts in Lena’s scenes of anything suggesting sex. Her bubble bath scene was cut. It was later used in a short here.

MGM was having a hard time finding non-stereotype roles for Lena Horne. They loaned her out to Twentieth Century Fox for a film called Stormy Weather. Most people still associated this song with Lena.

It’s hard to believe that when these movies came out, blacks had to sit in Jim Crow segregated upper balcony in the theater. Some southern theaters barred blacks altogether or admitted them only after midnight. Other theaters provided a “colored entrance” down a back alley. Horne also faced segregation at her own workplace. Debbie Reynolds wrote in her book that Lena wasn’t allowed to join the others in the MGM Commissary and would eat a sack lunch sitting outside the sound stage. Debbie said she would join her for lunch outside.

Theaters in the South refused to screen a movie with a black actress, except one in a subservient role, so Mayer resorted to just having Horne do cameo appearances in which she sang a couple of songs, which could be easily cut out in the South without disrupting the plot.

Horne appeared in more than 16 feature films and several shorts between 1938 and 1978. But she never had a leading role in her early films because of this problem.

The final straw with MGM came when they green-lit Show Boat in which a racially-mixed woman is married to a white man. She has been passing for white but her race is exposed by a jealous lover and it leads to her downfall. Lena wanted the part very badly. It was perfect for her and this would have been the best opportunity to give her that dramatic part she deserved.

But unbelievably, the Hollywood Production Code would not let a racially-mixed person be romantically paired onscreen with a white person. However, it was permitted that a white woman could pretend to be bi-racial and play the same role. So the role went to Lena’s good friend, Ava Gardner, who had to be made to look more black. Ava Gardner also had to practice lip syncing to Horne’s voice for the movie and wondered herself why they just didn’t give the part to her. In the end, the voice dubbed in the actual movie was someone else entirely. This must have been infuriating for Horne.

But through it all, Horne became a true civil rights hero and fought racism her entire life.

From nps.gov: “While entertaining troops at Fort Reilly, Kansas during World War II, Horne filed a complaint with the NAACP because African American soldiers in the audience had to sit in back seats behind German POWs. Horne financed her own travel to entertain black troops when MGM Studios pulled her off its tour.

In the late 1940s, Horne sued a number of restaurants and theaters for race discrimination and also became politically allied with Paul Robeson in the liberal organization Progressive Citizens of America. She joined Eleanor Roosevelt’s unsuccessful campaign for anti-lynching legislation and worked on behalf of Japanese Americans who faced discrimination.

During the anti-communist hearings in the U.S. Congress in the 1950s, Horne was among hundreds of entertainers blacklisted because of political views and social activism. In the 1960s, she performed in the South at rallies for civil rights, participated in the 1963 March On Washington, and supported the work of the National Council for Negro Women.”

Lena Horne died in 2010 at the age of 92. She was a multimillionaire unlike many of her counterparts from this era.